Lump-sum vs dollar-cost averaging

Imagine a scenario where you won a lottery or you inherited a quite load of money or you sold a property. You already know pretty much about investing in dividend stocks and your actual question is: "What if I invest all money at once. Is it better than investing periodically?"

Firstly, let`s take a look at well-known terms, that you should know in this kind of situation.

What is a lump sum (LSI)?

The lump sum investment is a commonly used term that indicates a payment of a large amount at once. You can find this type of payment mostly in cases like buying a property where you need a mortgage (and a bank requires a portion of the money upfront) or when you win a lottery as I mentioned before.

So now, we know what lump-sum means.

Lumpsum or Lump-sum or a lump sum?

What is the correct form of these words? Based on the Cambridge dictionary, it should be a "lump sum". But you can find many versions, especially with the dash between these words.

What is dollar-cost averaging (DCA)?

The exact opposite of a lump sum is a periodic payment. In terms of investing it`s called dollar-cost averaging. What does it mean?

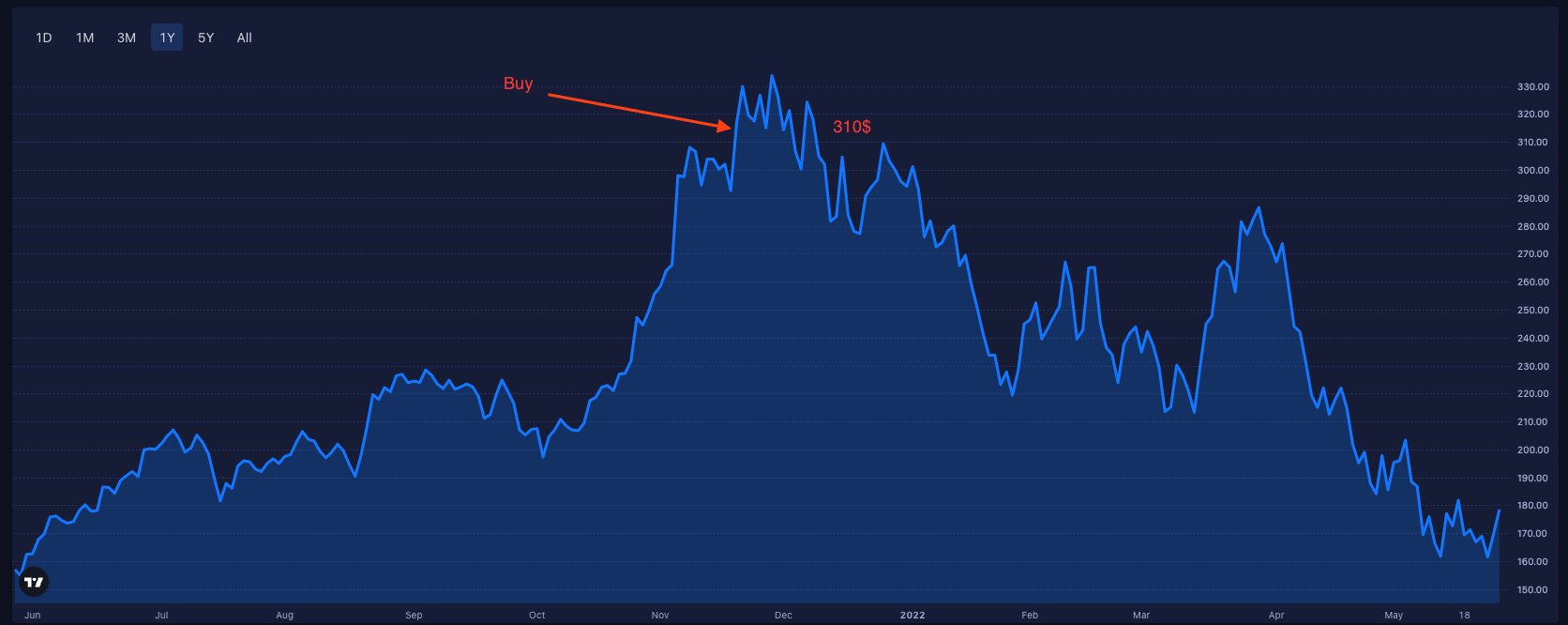

Imagine a situation - you have 2000$ and you buy an NVDA stock with a lump-sum approach at the end of October 2021.

(Note: Keep in mind that this is an example on a very short timeframe which is used only for a demonstration.)

(source: One of our friends is developing a great tool Strike.market with a Share of Search metric and other marketing-related info)

You bought 9 shares of NVDA stock for 210$ -> so now you have 1890$ in your portfolio. NVDA stock skyrockets from 210$ to 330$. Everything looks great. Your portfolio is sparkling with 2970$ at the begging of December.

Then the dark time kicks in and you end up with 1530$ (170$ per share). You lost 360$.

Dollar-cost averaging looks like this:

You buy shares only for 400$ each month (5 months of investment).

October 1 share for 210$

- 400-210 = 190$ for next month

November 2 shares (250$ per share)

- 400+190 = 590$

- 250*2 = 500$

- 590-500 = 90$ for next month

December 1 share for 320$

- 400+90 = 490$

- 490-320 = 170$ for next month

January 2 share (280$ per share)

- 400+170 = 570$

- 280*2 = 560$

- 570-560 = 10$ for next month

February 1 share for 240$

- 400+10 = 410$

- 410-240 = 170$ left

Overall investment: 1830$

Money that left: 170$

October share loss: 40$

November share loss: 160$

December share loss: 150$

January share loss: 110$

February share loss: 70$

Summarized loss with dollar-cost averaging is: 530$

So lump-sum is a better choice, right?

It depends. In our scenario, we invested in a bull race. The cost of each share was mainly at its peak which resulted in a catastrophic situation.

Let`s take a look at this picture.

Take your 2000$ and go to the market. You buy 6 shares for 310$ per share, which is 1860$ (140$ left). Now the market goes down and you end up with 1020$ ... which is an 840$ loss. Do you see the difference? It really depends on when you buy shares. You can hit the perfect period and get rich and you can also do your worst decision ever and end up broke.

I think that all of us have this hidden urge to invest more in the bear period. Yes, you can`t predict future performance on historical data, but you can definitely tell that some stocks are going to hell because of their bad historical performance (basically investors lost their interest and credibility in this type of company). Also what you can do - you can analyze stocks more deeply and see their approach and how they perform, what is their strategy.

Based on your best common sense you can diversify as much as you can and pray for the best and sometimes try to risk more and add more money, maybe luck could help you get a better return in the long run.

What are the main dollar-cost averaging benefits?

The main benefit is that you lower overall risk in the long run. It always depends on a given time frame. As you can already tell, with dollar-cost averaging you can sometimes make less money than with lump sum. But it`s always good to be aware of the risk you want to accept.

Take a look at this study: https://static.twentyoverten.com/5980d16bbfb1c93238ad9c24/rJpQmY8o7/Dollar-Cost-Averaging-Just-Means-Taking-Risk-Later-Vanguard.pdf

Here is a quick summary:

Out of the 1,021 rolling 12-month investment periods we analyzed for the U.S. markets, LSI investors would have seen their portfolios decline in value during 229 periods (22.4%), while DCA investors would have seen such declines during only 180 periods (17.6%). Furthermore, the average loss during those 229 LSI periods was $84,001, versus only $56,947 in the 180 DCA periods. The allocation to cash during the DCA investment period decreases the risk level of the portfolio, helping to insulate it from a declining market.

...

Clearly, if markets are trending upward, it’s logical to implement a strategic asset allocation as soon as possible because it should offer a higher long-run expected return than cash. Historically, a long-term upward trend has persisted for both equities and bonds, probably attributable to positive risk premia in the markets. In other words, positive returns have compensated investors for taking risks, hence the upward trend in those markets and the resulting probabilities of success for LSI. So, to the extent that an investor believes the positive risk premia are likely to exist in the future, LSI would remain the preferred method for investing an immediately available large sum of money. But if the investor is primarily concerned with reducing short-term downside risk and the potential for regret, then DCA may be a better alternative.

To be comfortable with either strategy, an investor must be fully aware of the fact that historical averages are only a guide—it is still possible for LSI or DCA to underperform or even lose money in any given period. If an investor is uncomfortable with the risks associated with a given market entry strategy, it may imply a low willingness to take risk in general, and if so, we recommend revisiting the target asset allocation to ensure that it appropriately addresses risk tolerance levels and investing goals.

What do you think?

What is the right dollar-cost averaging frequency?

Daily, weekly, monthly? Which way should you go?

Firstly, you have to consider broker fees. With no fees (and in an ideal world), you should go for weekly investments. Based on more "data input", you have a better chance to lower risk even more, because everything is averaging.

But the market behaves differently, you pay broker fees, and you also may have a different currency in your country (like us in Czechia) ... Based on all these thoughts, many of us end up on monthly basis.

How to do dollar-cost averaging?

As described before, pick an amount of money that you are able to invest periodically and be consistent with this type of strategy.

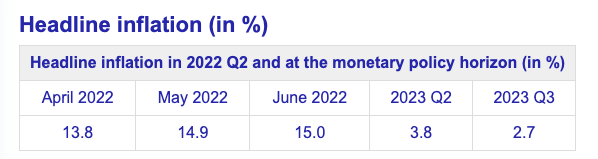

What if I choose dollar-cost averaging but inflation takes the cream?

This is a whole different story. Let`s say you are in between two millstones. On one side you take risk of losing money because of the bear market and on the other side, you take risk of almost 15% inflation burning your money before your eyes (a small example from Czechia).

(source: https://www.cnb.cz/en/monetary-policy/forecast/)

Still, if we take the same example with NVDA stock - in all cases the performance is bad, but in the case of a total sum of money that you lose, DCA (dollar-cost averaging) performs better. The power in beating inflation is in the right choice of stock that performs at least 15% in a year.